Ranch with a view, rancher with a vision

With help from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) in Texas, Houston Dobbins is working to maintain and improve his piece of the landscape.

Story and photos compiled by Wade Day, Public Affairs Specialist, San Angelo, Texas

Ranch with a view, rancher with a vision (ArcGIS Story Map)

Houston Dobbins manages his family’s 2,500-acre ranch in Val Verde County, near Del Rio, Texas. An area of transition, located between the hill country and the Trans-Pecos region, it is referred to as South Texas brush country. The area’s vegetation is varied, a mix of shrubs, cactus and low growing grasses. With a desert-like climate, everything living here must be able to withstand the rigors of this area.

Though challenging, it also contains unexpected beauty and hidden gems of history.

With help from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) in Texas, Dobbins is working to maintain and improve his piece of the landscape.

From the past

Dobbins has been managing his ranch for more than six years, but this fourth-generation rancher has family connections to the property that began long before. Dobbin’s great grandfather, a Swiss immigrant, purchased the property — site unseen — from a newspaper article in 1890. The land was passed down to Dobbin’s grandparents and eventually, to his mother.

“It’s nice being out here on the ranch, it’s just something I always enjoyed doing,” said Dobbins.

His great grandfather’s gamble proved to be a smart one, the desert-like property has an unexpected resource.

The ranch has 30 miles of waterfront that rolls down to Amistad Reservoir and the Rio Grande River. For an area that averages less than 20 inches of rainfall yearly, this water source is precious and makes ranching possible.

“Being located along Lake Amistad, I don’t have to worry about water. It helps my operation as there’s a constant source of water,” said Dobbins.

Though the land has remained unchanged, the ranch’s livestock operation has transitioned over time.

Cattle, sheep, and goats have all been raised on the ranch at some point. Dobbins grew up raising Rambouillet sheep and Spanish goats. He recalls it being everything from a show lamb operation to more commercial animal production, which it is now. Currently, most of the livestock are Dorper sheep, a breed more suited to arid regions.

Cultivating a partnership to practice conservation

Though not new to ranching when he took over the family operation, Dobbins was new to being the lead at the ranch and making all the decisions. His initial struggles included several things, but infrastructure was his main concern.

He reached out to the NRCS and Val Verde County District Conservationist Reagan Gage for assistance with managing his family’s property.

Both men agreed the ranch needed work.

“NRCS has been able to help tackle issues with the landscape more than anything,” said Gage. “Our first meeting was getting together and looking at the ranch. Being able to see what kind of (brush) species we’re working with, what the situation was, and what the soils were like to narrow it down. We were able to find the best recipe to help meet his goals.”

Dobbins utilized the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) for the conservation work he has accomplished on the property. EQIP provides technical and financial assistance to agricultural producers to address natural resource concerns. NRCS works one-on-one with producers to develop a conservation plan that outlines conservation practices and activities to help solve on-farm resource issues. EQIP helps producers make conservation work for them.

Bringing his fences up to par was a large part of that process.

Without the fences, Dobbins could not have an effective rotational grazing system. Planning and installing cross-fencing allowed for better rotational grazing, further improving the health of the land and keeping his livestock thriving.

Another major challenge for the ranch was brush management.

“Houston’s place was pretty much brush dominated,” said Gage. “It had some grass, but not as much as the potential — not as much as Houston would’ve like to see. And so, it’s been very rewarding to see the difference before and after.”

They decided to use chemical control methods to attack the brush problem.

“Reagan got me interested in the idea, telling me how beneficial it would be towards my operation,” said Dobbins. “It would help me with my stocking rates, promote grass growth and kind of get rid of things that are in over abundance.”

The recommendation for chemical control also came from the challenges Gage saw.

Traditional mechanical methods can be time-consuming, expensive and invasive. In arid areas, less ground disturbance is often beneficial for recovery. For his situation, chemical control was the best solution.

“We had an area that is very dry, rocky, often steep slopes — country that you would really have a hard time adapting any mechanical brush work,” said Gage.

They targeted species like Cenizo, Guajillo, White Brush, Black Brush and prickly pear, all common to the area.

The changes in management and infrastructure have worked, providing several benefits to the ranch.

“It’s helped me with the diversity of plants for the sheep and goats,” said Dobbins. “We’ve been months without any rain and the sheep are still healthy and a lot of it’s because of the work we’ve done.”

Ancient art within the rocks

The property holds another resource as special, or maybe more so, than the rest.

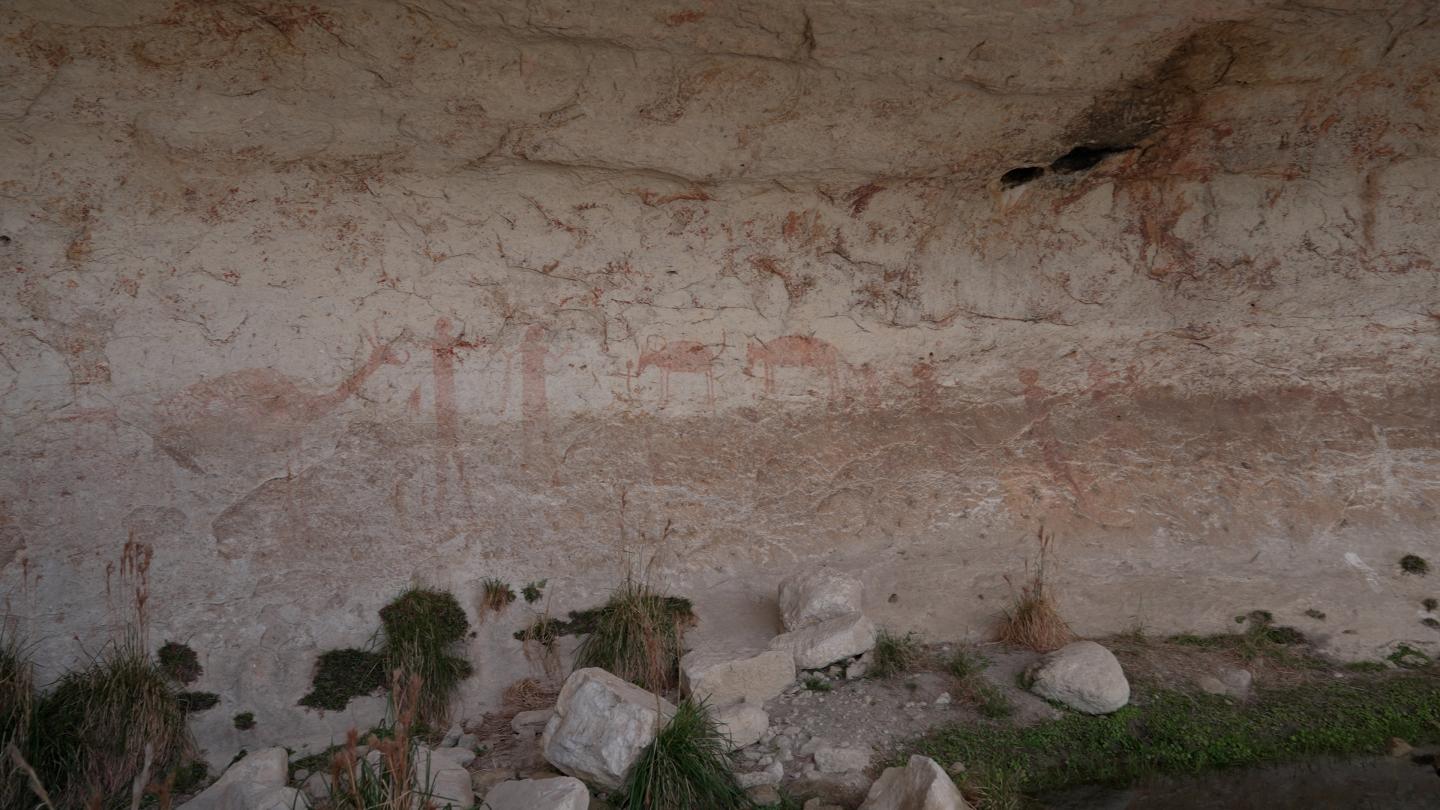

The property is home to several caves, some of which have numerous Lower Pecos Region Rock Art or pictographs, along their walls.

The pictograph sites found on the Dobbins’s ranch are estimated to cover a time span from the 19th century to over 10,000 years ago. They demonstrate some of the earliest forms of human communication and storytelling.

“The Indians that inhabited (the area), they wanted to live here for a reason,” said Dobbins.

The cave walls reveal red monochrome figures, including people and animals of various size and scale. The artwork tells the story and records the history of the people who called it home.

While the cave art has an incredible amount of historical value, it is also something that Dobbins likes to share.

“I try to bring as many people down here as possible, especially friends,” he said.

Past, present, and future

Vision, commitment, and lessons learned are all part of carrying on the legacy of those that came before him.

Whether it’s with the animals, the land, or the history of the area, Dobbins will continue to evolve on his journey as a rancher and becoming part of its story.

“Being here, (this ranch) has a deep history of the people that inhabited this area,” said Dobbins. “Its natural resources — the water, the plants, and the diversity of animals that live (here) — it’s just rich in history. That’s what draws me to being around here. It’s a family history.”

Knowing where you came from is the first lesson but making it work may be the hardest.

Dobbins’s attitude, determination, and willingness to learn and implement new ways of doing things has proven to be a winning combination.

“With ranching you have to care about the animals that you’re raising and give them the best opportunity you can to survive and thrive in this kind of area,” said Dobbins. “Being outside every day, working with the sheep and goats, it’s a rewarding job. You actually get to see things progress and there’s always something you could be doing better.”

The assistance and collaboration with NRCS have helped to bridge that gap.

“Whenever I have an idea, or something that might work, or something I’ve heard about, I talk to the NRCS,” said Dobbins. “(They) know what other producers are doing and what works in this area — awesome to bounce ideas off of.”

The same can be said of Dobbins as well.

“It’s been great working with Houston because he’s been very open-minded and willing to adapt to new ideas,” said Gage. “He wants the best for the land and that’s what you want to see when you work with someone.”