Advancing Conservation in Indiana Through Partnerships

Partnership demonstrates how two conservation practices working together can make big impact in improving water quality.

For the last 30 years, Brian Romine has watched the area around his farm in Kosciusko County, Indiana transform. As the climate has changed, what used to be 100- and 50-year storms have become a nearly annual occurrence. Those drops of rain fall on his 1,500 acres of farmland watering his corn and soybeans that help to feed the nation. But what isn’t used by the crops, or absorbed by the soil, runs off into ditches, streams and rivers like the Tippecanoe and the Wabash before joining with the Mississippi River and flowing south to the Gulf of Mexico.

As that water flows, it may take with it eroded soil from fields, as well as nitrogen and phosphorus, which are beneficial to farmers, but in excess, they are harmful to waterways.

Romine implemented conservation practices on his own land by no-tilling for the last 30 years and planting filter strips along the Shatto Ditch — which runs through his farm for part of its more than four-mile length before draining into the Tippecanoe River — but it wasn’t enough. Over the years, runoff from his land and all those in the watershed had started to fill the ditch and the river with sediment and there are now places where he estimates you couldn’t even travel along the river in a canoe.

While Romine was noticing the issues with the Shatto Ditch and Tippecanoe River, Jennifer Tank had heard the complaints from further south for a long time. The University of Notre Dame Galla professor of biology said each year she hears and reads reports from the Gulf of Mexico blaming midwestern farmers for the dead zone that stretches along the coast of Louisiana. That same rainwater Romine watched fill the ditches, streams and rivers in Indiana carries potentially harmful excess nutrients south to the Gulf of Mexico helping to create an area each summer of nearly 8,000 square miles with little to no oxygen, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

So, in 2006 Tank partnered with county Soil and Water Conservation District, along with The Nature Conservancy, to see if they could make a tiny impact on the nutrients flowing south and demonstrate practices that could be implemented throughout the entire region. The first step was to transform a half-mile stretch of the Shatto Ditch in Kosciusko County into a two-stage ditch, a practice that had recently been introduced in the tri-state area of Indiana, Ohio and Michigan.

The goal with the two-stage ditch, Tank said, is to enhance removal of dissolved nutrients that runoff from farmland, as well as treat tile drain outflows and improve the water clarity before it reaches its endpoint in a waterbody.

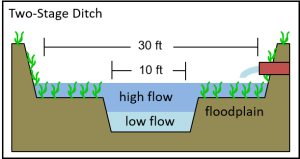

“Conventionally managed ditches are built and/or maintained to have trapezoidal channels with steep banks that can be vulnerable to bank erosion,” Tank said. “The two-stage ditch transforms the steep ditch banks into vegetated, mini-floodplains and results in an increase in channel stability, reduced bank erosion and provides added water quality benefits.”

In 2013 they began to think bigger. Instead of just studying how a section of two-stage ditch could impact water quality, they decided to pair the two-stage practice in the waterway with cover crops planted throughout the Shatto Ditch watershed and measure how the paired conservation practices reduce the runoff of sediment, nitrogen and phosphorus into the Tippecanoe River. This innovative idea launched a partnership between the University of Notre Dame, Indiana University, the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), the Nature Conservancy, as well as the Kosciusko County surveyor and Soil and Water Conservation District.

The partnership, which is known as the Indiana Watershed Initiative (IWI), was able to secure funding for cover crops and two-stage construction in the Shatto Ditch watershed through NRCS’ Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP). Through the RCPP funding and matching funds provided by the Walton Family Foundation and the Indiana Soybean Alliance, the partnership was able to extend the two-stage ditch from its original half-mile length to a final length of 4.1 miles.

“We did every foot of what we can do in terms of farmer participation,” Tank said of the ditch while adding that it is the longest two-stage in the world.

The program also enabled them to fund the planting of cover crops for participating farmers for five years. Before the RCPP program, 13% of the farmed acres in the watershed were planted with cover crops in between cash crop seasons. During the five years of the Indiana Watershed Initiative, 62-68% of the acres in the watershed were planted with cover crops.

The goal of IWI was to study how combining the two conservation practices could help local farmers and protect nearby waterbodies by keeping more nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil. And by doing that, it also helps the entire water system because less of those nutrients make their way into streams, rivers and eventually the Gulf of Mexico. Cover crops hold nutrients in the soil helping to reduce what flows out through the tile drains during natural drainage, and then the two-stage ditch polishes off those nutrients that do make it to the waterway.

Along with the implementation of the paired conservation practices, the five-year program included comprehensive monitoring and data collection of the water and soil in the watershed. Researchers from the University of Notre Dame and Indiana University made trips out to the watershed every two weeks to test the water flowing from the tile drains. Researchers also conducted soil sampling in the area twice a year and provided all the data back to farmers.

The access to the data was a main selling point for Mike Long who farms 3,000 acres of corn, soybeans, wheat and rye with part of his operation falling in the Shatto Ditch watershed. He had been no-tilling his farm since 1996 and planting cover crops off and on for 15 years but jumped at the opportunity to participate in this study, allowing him to gain access to data collected on his farm and helping him increase his cover crop acres to include his entire operation.

“I figured this would be an excellent way for us to monitor or to get some free testing of what is actually happening in our field,” Long said. “So, that's kind of what excited me about it and I said in the future if we've got a problem with something down the road we have a benchmark that we can go by, and if we are creating a problem, we will know.”

Including Romine and Long, about 10 landowners in the Shatto Ditch watershed took part in the cover crops study and having the two-stage ditch built on their land. Funding for the cover crops ended in 2019, and while implementation fell from 68% during the RCPP period to 22% this year, this is the first year without direct payments to farmers.

Todd Royer, an associate professor of environmental science at Indiana University-Bloomington, said the hope is farmers will return to cover cropping in the future after seeing the impact of stopping the practice. In the end though, the coverage in the Shatto Ditch watershed is still at twice the state average even with the post-RCPP drop. For the program to be truly impactful and reduce the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, farmers themselves will have to buy in to the conservation practices as Romine and Long did by continuing to cover crop their fields even without the direct payments, Royer said.

The five years of the study convinced Romine and Long that not only were they improving the health of the river by keeping sediment and nutrients from running into the waterways, they were also increasing the health of their soil.

“I didn't feel that we could increase the organic matter that quickly, and also get the yield response as quickly as what we have,” Romine said. “My takeaway is I'm sticking with cover crops. I may do something different with the mix as we learn more, but right now, cover crops are going to be on there as long as I'm involved with it.”

With cover crops and no-tilling, Romine said he is seeing less erosion on his fields and some of the best yields in the county, giving him comparable yields to parts of the state with “much, much better dirt than what I have.”

Long had instituted cover crops on parts of his field before the RCPP started, but now plans to continue with cover crops on his entire 3,000-acre operation. A former member of the country drainage board, he has also become a vocal advocate for two-stage ditches after seeing the impact the Shatto Ditch had on nutrient loads in the water and the reduced maintenance it requires compared to a traditional ditch.

“Our fertility is going up without additional fertilizer,” Long said. “So, I assume that's the biology releasing it … And I've also seen organic matter continue to rise. We're more weatherproof than we used to be. Like this year, we've had this major dry spell toward the end. That's really not affected us that much.”

While the farmers can see the impact of the programs in yields, the researchers have found proof in the monitoring data that combining the two-stage ditch with “saturation level” cover crops helps both farmers and the health of adjacent waterways. In the Shatto Ditch watershed they saw large reductions in the amount of nitrate-nitrogen and dissolved phosphorus running off fields, through tile drains and into the ditch. The two-stage ditch was then able to “polish off” some of those excess nutrients and sediments, further reducing what made it out if the ditch and into the rivers.

“Our nutrients losses from the Shatto are reduced because of the conservation at saturation levels,” Tank said. “So, what I think we were trying to show with the demonstration project is that you can get success that is both beneficial to water, as well as farmers, by simple approaches. Cover crops and two-stage ditches, they're not complicated. It can be challenging to coordinate implementation, which takes strong partnerships, but once they are in, the way they work is not complicated.”

The research study in the Shatto Ditch watershed enabled them to gather compelling data about conservation practices that they couldn’t have captured anywhere else, Royer said. To show the real-world impact of the practices, the experiment needs to take place on working farms, not in an experimental setting. The partnership also enabled them to fund and study the impact of high cover crop usage, which may not have been possible in other areas, he added.

Following five years of research that included frequent trips out to the two watersheds, Tank said she, “Wouldn't trade it for a second, in terms of what we learned. It's what we had to do in order to demonstrate at this adoption level what the potential is,” when two practices that had been used separately are combined into one comprehensive conservation plan.

Additional Information

Regional Conservation Partnership Program - Indiana

The Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) is a partner-driven approach to conservation that funds solutions to natural resource challenges on agricultural land.

Learn MoreINDIANA NRCS HOMEPAGE

For more information about NRCS programs offered in Indiana and how experts throughout the state can help you address natural resource concerns on your land, visit the Indiana NRCS homepage.