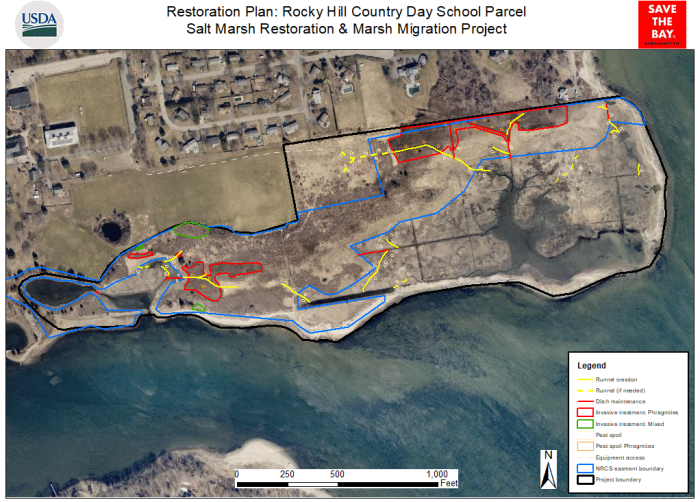

NRCS is partnering with the Rocky Hill Country Day School, Save the Bay and the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management's Mosquito Abatement Program to restore salt water marshes and facilitate marsh migration at the mouth of the Potowomut River in Warwick, Rhode Island.

NRCS worked with the Rocky Hill School to protect 22 acres of salt marsh and wetlands on their 85-acre property with a Wetland Reserve Easement. The Wetland Reserve Easements component of the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program provides habitat for migratory waterfowl and other wetland dependent wildlife, including threatened and endangered species, and improves water quality.

The degraded salt marsh was identified for restoration and marsh migration corridor creation to mitigate the impacts of accelerated sea level rise and human activities (agricultural embankments and ditching for historic farming activities).

Rocky Hill School's salt marsh is also home to two wildlife species of concern: the Northern diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin terrapin) and the Saltmarsh sparrow (Ammodramus caudacutus). These two species are listed as Rhode Island's Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the 2015 Rhode Island State Wildlife Action Plan.

The Rocky Hill School property is one of only two confirmed locations in Rhode Island that support diamondback terrapin nesting. It also has one of the highest current population density scores for saltmarsh sparrows within Rhode Island. Saltmarsh sparrow populations have been declining at a rate of 9 percent per year; it is at risk of extinction within 50 years or less, according to the Saltmarsh Habitat and Avian Research Program.

The Wetland Reserve Easement program is an excellent tool for saltmarsh sparrow conservation because it provides for both easement acquisition and the use of NRCS conservation practices to conserve or create “high marsh” areas that are critical for saltmarsh sparrow nesting success. Saltmarsh sparrows nest only in high marsh areas where their nests can have some protection against monthly high tide levels. This has become the most critical issue across their breeding range, as sea level rise reduces the amount of high marsh available.

Background

The Rocky Hill salt marsh was showing signs of degradation — conversion of the marsh platform from high marsh species to more salt tolerant low marsh species, Spartina alterniflora (saltmarsh cordgrass); expansion of shallow impounded water on the marsh platform; vegetation thinning and dieback; peat subsidence; and expansion of invasive Phragmites australis and invasive woody species.

Marshes lose surface elevation from persistent waterlogging, which causes a series of cascading processes: reduced plant growth > vegetation die off > root decomposition that creates voids in the root zone > collapse and further surface subsidence of the marsh platform. Salt marsh ecologists refer to this process as waterlogged subsidence trajectory.

Similar conditions have been documented throughout the Narragansett Bay watershed and southeastern New England. Increased water impoundment on marsh platforms is due in part to accelerated sea level rise and legacy human impacts. Based on regional data from the Narragansett Bay Estuarine Research Reserve, salt marshes are not building enough elevation to keep pace with the accelerated rate of relative sea level rise in Narragansett Bay (5.2 mm/year).

In addition to the expected habitat benefits for the terrapin and sparrow species, tidal flow restoration at Rocky Hill will help improve the salt marsh’s resilience to sea level rise. Salt marshes also provide important nursery habitat for fish species that are food for larger, commercially-important fish in the New England.

Wildlife species of high conservation concern

Saltmarsh Sparrow

Saltmarsh sparrows (Ammospiza caudacuta) breed in salt marshes in all coastal New England states including Rhode Island. Their populations are declining due to loss of high marsh habitat where they nest due to sea level rise and past human impacts. Nest flooding is the main driver of population declines.

Salt Marsh Sparrow Conservation Plan - Atlantic Coast Joint Venture

Northern Diamondback Terrapin

Northern diamondback terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin terrapin) are State Endangered in Rhode Island and are uncommon in the state. Their population has suffered greatly due to poaching, overharvest and habitat loss. They are found in estuaries, coves, barrier beaches, tidal flats, and coastal marshes. They spend the day feeding and basking in the sun and bury themselves in the mud at night.

Terrapin Conservation Story - Narragansett Bay Estuary Program

Project Goals and Action Items

Goals

- Restore marsh hydrology: Drain impounded water off the marsh platform to improve salt marsh health and function by excavating shallow runnels and selectively maintaining existing ditches to facilitate salt marsh revegetation.

- Reduce invasive exotic stands of Phragmites australis: reduce impounded brackish water on the marsh surface, mechanical mulching and mowing.

- Facilitate future marsh migration (due to sea level rise) into low lying uplands by draining impounded water in the marsh migration corridor, controlling woody invasive plants, and planting native salt-tolerant plants.

- Enhance nest sites for the endangered Diamondback terrapin and Saltmarsh sparrow.

- Reduce mosquito-breeding habitat: drain impounded water too shallow to support fish and promote fish predation of mosquito larvae by creating shallow runnels.

Conservation Practices

Wetland Restoration – Tidal Channel Restoration (CPS 657) to restore hydrology by excavating existing ditches that were filled in with sediment by using a very low impact excavator. Channel maintenance will reduce the height and vigor of invasive Phragmites australis by draining impounded brackish water from the marsh surface.

Wetland Restoration – Runnels (CPS 657): Other “soft” areas of the marsh (due to sea level rise, unnatural ponding and subsequent die-off of marsh plants) too sensitive for low-impact equipment will have small channels, or runnels, hand-dug to further restore natural tidal flows by draining impounded water from the marsh platform. Unlike ditches, runnels are shallow - only up to 12 inches deep. They allow vegetation to recolonize die-off areas by reducing root zone saturation and optimizing hydrologic connectivity between standing water on the marsh and adjacent natural creeks or ditches.

Obstruction Removal (CPS 500) of a “sill” of broken wall fragments and accumulated

sediment that is impeding tidal flow at the eastern edge of the property.

Wetland Wildlife Habitat Management – Turtle Nest Site Creation (CPS 644): remove vegetation and scarify soils on several small sites across the easement to create about 0.5 acres of turtle nesting sites.

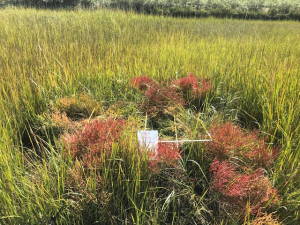

Wetland Wildlife Habitat Management – Sparrow Nest Site Creation (CPS 644): place peat clumps excavated for runnels next to one another to create marsh platform microtopography or microhabitats – small patches or islands of higher elevation that flood less from extreme tides and larger rain events – to increase saltmarsh sparrow breeding productivity and nest success.

Restoration Progress

Invasive weed treatment began by cutting Phragmites australis to reduce its height, reducing impounded water with newly dug runnels, mechanical mulching and successful cutting. Limited herbicide applications were applied to the stumps of woody invasive plants [Rosa multiflora, honeysuckle (Lonicera sp.), autumn olive, (Elaeagnus umbellate), buckthorn, (Rhamnus sp.), and bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) and native salt tolerant species were planted. Four large, mature specimens of tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima)] were also removed.

Diamondback terrapin nesting locations were selected by the state herpetologist based on their proximity to water, gentle slope, soil type, sun exposure, and limited physical barriers. The nesting sites were enhanced through invasive plant removal, soil scarification and sand amendments.

Monitoring and Maintenance

Save the Bay staff established photo stations and vegetation monitoring transects in the salt marsh and marsh mitigation corridor. They conducted pre-restoration vegetation monitoring in Fall 2022, will continue to monitor vegetation response and document terrapin activity, and will conduct post restoration monitoring for two years following completion of the restoration project.

Save the Bay also installed four game cameras to check predation of terrapins and determine if additional actions are needed.

To ensure necessary drainage, the new runnels will be maintained by hand by Save the Bay staff and volunteers in consultation with RIDEM’s Mosquito Abatement Program.

More Info

- “In the Wake of the Water,” Will Steinfeld, Places Journal, December 2024.

- Save The Bay Revives, Fortifies Waterlogged Warwick Marsh | ecoRI News, Feb. 5, 2024.

- Restoring a Marsh at Rocky Hill CDS | East Greenwich News, Jan. 16, 2024.

- Save the Bay, Rocky Hill give marsh a fighting chance | Warwick Beacon, Dec. 18, 2014.

Additional Information

Wetland Reserve Easements - Rhode Island

NRCS in Rhode Island is now accepting applications for ACEP Wetlands Reserve Easements (WRE). Applications that meet eligibility and ranking criteria in ACEP-WRE targeted areas received by October 3, 2025, will be considered for our first round of FY 2026 funding.

Learn MoreAgricultural Conservation Easement Program - Rhode Island

The Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) helps landowners, land trusts, tribes, and other entities to protect, restore, and enhance wetlands, grasslands, and working farms and ranches through conservation easements.

Learn More