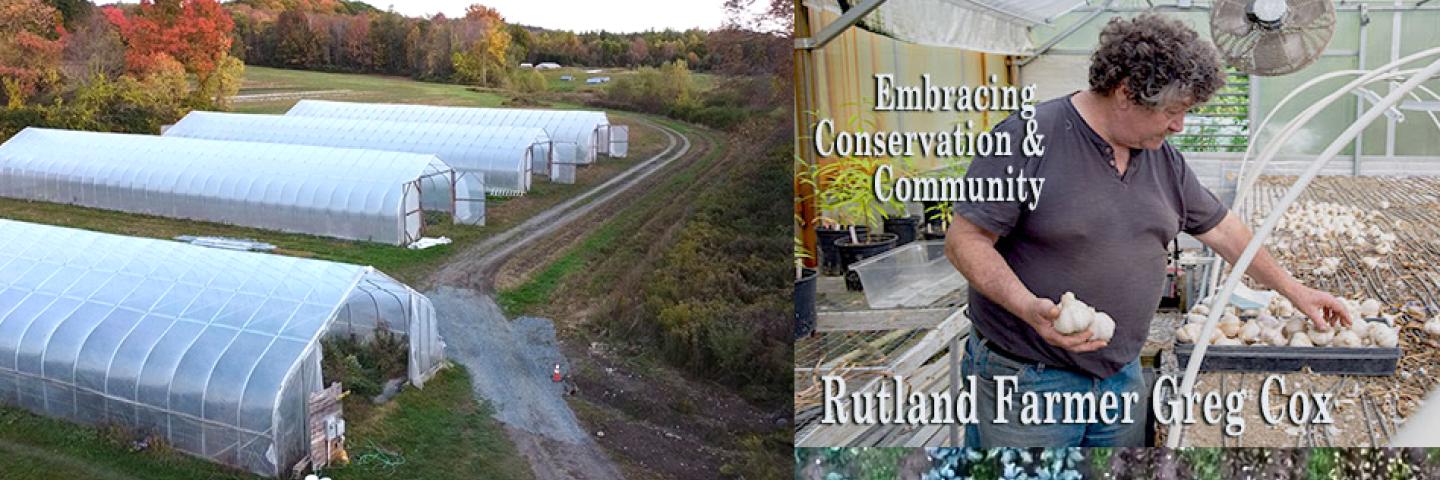

Vermont Farmer Greg Cox Embraces Community and Conservation

Greg Cox owns and operates Boardman Hill Farm in West Rutland, Vermont. His diverse farm includes ten acres of organically certified fruits, vegetables, flowers, and he manages a popular Community Supported Agriculture (CSA).

His stewardship led him to work with the conservationists at the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) who helped him implement a system of conservation practices through the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). For example, he installed four high tunnels to protect plants from extreme weather and enable season extension by growing earlier in the spring and later into the fall. Mr. Cox credits the high tunnels for helping make a popular winter farmer’s market in Rutland a reality. “You can dine all year long,” he says. “The high tunnels make it possible. It’s the single biggest reason we can have a year-round food system in the Northeast, because things don’t grow during our cold, dark winter season.”

His conservation plan also included planting winter cover which helps curb erosion between harvests and prevents nutrient runoff on 22 acres of his land. He also addressed inefficient water use on irrigated land with a high pressure underground plastic pipeline, micro-irrigation, mulching, pest management and an irrigation water management system. His farmstead energy improvement plan reduces emission of greenhouse gases and reduces heat in an existing greenhouse at his farm. A controller system in the greenhouse also helps monitor conditions while a root zone heating system creates ideal temperature conditions needed to germinate crops for the coming growing season.

And when he isn’t busy getting his hands in the soil, Mr. Cox illustrates his commitment to his community and sustainability. In 2016, he established a one-acre solar farm with forty participating families. “It was the largest single-phase solar project in Vermont,” he says. His effort received widespread acclaim, won several awards and become a national model for similar solar development efforts. He was even recognized with a Governor’s Environmental Excellence Award. “This project is resilient and sustainable. Energy is a resource. Now I don’t feel as guilty when I see my electric bill come in for my infrastructure.”

He says the financial and technical assistance he received from USDA for his EQIP conservation plan has been invaluable. “I couldn’t have afforded to put in the benchtop heating system in the greenhouse without the EQIP assistance,” he explained. “It’s not just funding, but also the education you get from having conservationists analyze and tell you why and how, and that’s been really helpful for me.” As a conservation farmer, Mr. Cox embraces his operation as a natural resource and says he strives to “reduce the inputs and sustain outputs.” He believes that stewardship will pave the way for future generations. “I hope my son and my grandkids will have the capacity to use this farm and it will continue to produce food for our community,” he said.

In 1982 he purchased the land he farms now and became one of the first certified organic farms in the area. But he doesn’t do it alone. He farms with his twenty-four-year-old son Avery who is eagerly following in his footsteps. The Castleton University biology student shared his passion for conservation last year at the United Nations where he was invited to speak at a World Soil Day event. At the event, he noted the benefits of reduced tillage and cover cropping during his comments saying of the practices, “they allow the soil to be kept locked together within the roots and reduce the loss of soil organic carbon.”

Mr. Cox is outspoken about his farming philosophy and passionate about his role in protecting and improving natural resources. In describing his approach to farming, he says, “We almost border on regenerative, and biodynamic, where I don’t believe life is linear, it is more circular, so the crops we get out of the field that don’t make the grade, we feed to our animals, and we compost it, and spread it on field. We treat this farm as an ecosystem, so we don’t have to use inputs from outside. Our goal is to be a complete functional system so conservation is critical because it enables us to be more regenerative, more resilient, and more sustainable.”

In a state where the locavore movement was already solid, the pandemic has put an even greater focus on local agriculture and the availability of fresh produce in Vermont. In 2019, Vermont had the highest direct sales from farms to customers per capita nationwide. He has noticed an upward trend since the start of the pandemic. “With more people eating at home now, they are putting more thought into their health and their food. Previously, we relied heavily on wholesale and restaurants, but I had to adjust when everything shut down, “he explains. He says that the pandemic has been a change agent for agriculture and local food systems, and reflects, “it has given us the ability to think and make positive changes in our lives and other people’s lives.”

As co-founder of Rutland’s Vermont Farmers Food Center, he has been instrumental in helping Vermonters access locally produced food through education, market expansion, and market access. He helped organize a year-round farmer’s market and as a result was recognized in 2016 as Business Person of the Year by his local chamber of commerce. “When we reopened the farmer’s market this May, I hadn’t seen numbers like that in a decade. Local citizens came out and were really interested in buying local food. Sometimes it takes a critical point, like the pandemic, to evaluate and reassess and make a change in your own life and I am hoping it’s not a temporary change and I don’t think it is,” he said.

Born in Queens, New York, he moved to Long Island with his family at the age of eight. He then attended college at Johnson State in Vermont to be an educator. But it was his experience in Vermont, and his connection to the environment and the landscape of the Green Mountain State that motivated him to choose farming as a career. He operated a farm in Wallingford, Vermont, from 1975-1982, and developed a fondness for Rutland County. This was also a time when farmers markets were emerging but, “local food was not yet on the radar of Vermonters,” he reminisces. “When I started farming, there wasn’t much help, so my teachers were books, and I read a lot, figuring out what organic was, and learning about regenerative agriculture.” He has also dedicated time and effort to mentoring others by teaching agricultural classes at Green Mountain College and using his own farm as a teaching tool for aspiring young farmers.

If you spend a few minutes with this farmer, there’s no doubt he loves what he does and won’t be stopping anytime soon. “Farming is more than a financial transaction or a business. It’s critical to human health,” he says. His belief that health is ultimately tied to the food we eat and how it’s produced guides his farming principles. “Our health is nutrient based and that starts with soil.” This is why he has embraced conservation and remains committed to improving and protecting soil and water quality. “For me, farming is part philosophical, part humanitarian, part economic, but I wouldn’t be farming if all I was worried about is extrapolating and making sure every crop I put in the ground would net 35,000 dollars,” he explains. “I would go and make money somewhere else, but this is who I am, and this is my life.”